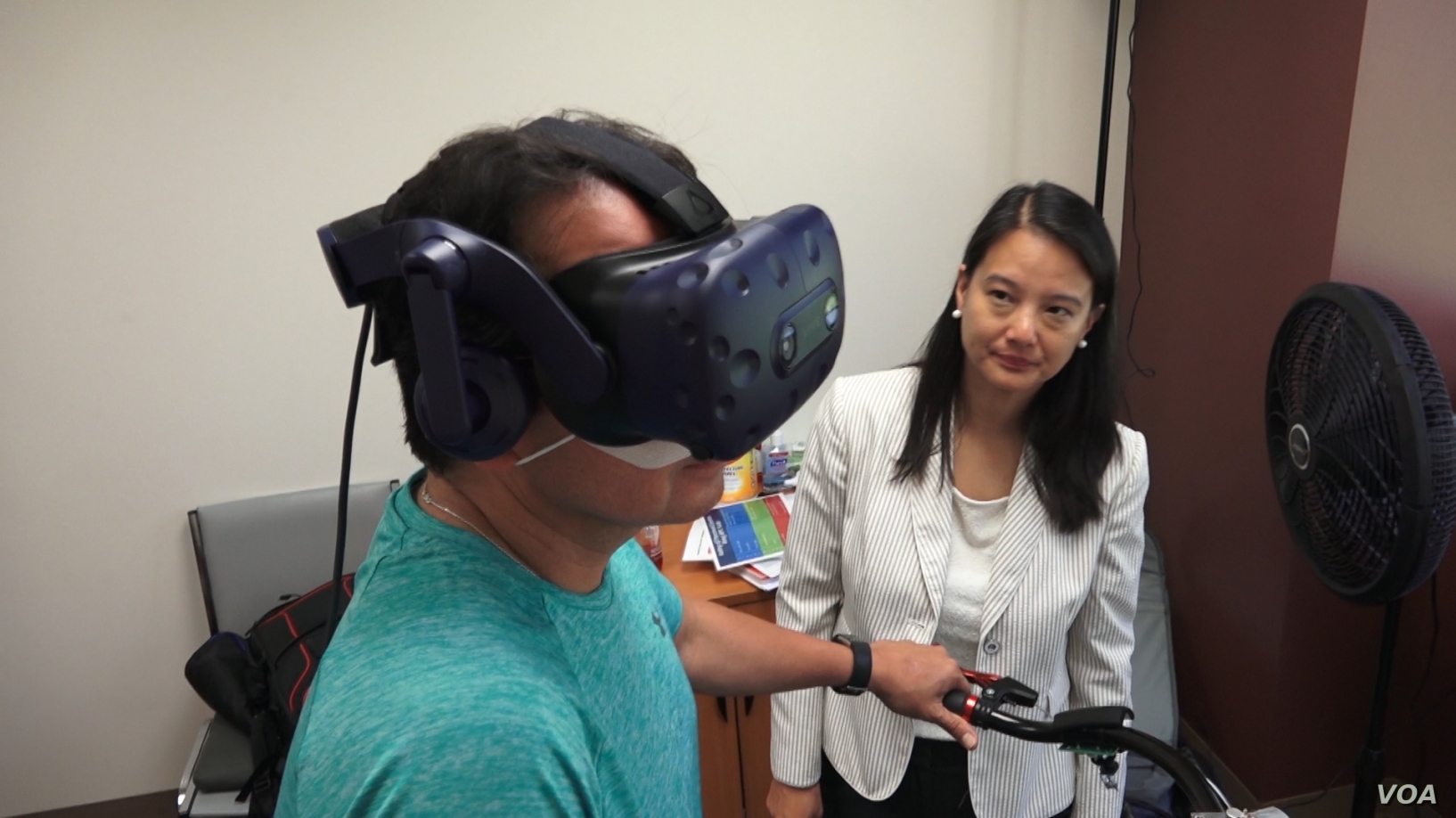

For three days a week, Wayne Garcia has been getting an unconventional workout. He starts by putting on a virtual reality (VR) headset. He then gets on a specially designed exercise bike and starts peddling. He is taking part in a study at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine to see if a dose of VR can help prevent age-related cognitive decline and dementia.

“It’s very scary that one day that could be me. Grandparents both had dementia. My father, he had dementia, as well, and my mom has dementia,” said Garcia, who painfully remembered his father reading the newspaper upside down and almost setting the house on fire by putting a towel on the heater.

“Just the sadness — you remember what your dad was like, what your mom was like when they were all good, and then the decline now. And now you’re taking care of them rather than when they used to take care of you,” Garcia said.

Preventing dementia

Garcia is participating to see if using virtual reality concurrently with exercise can help prevent dementia in the future.

“The actual diagnostic definition of dementia is when a person is no longer able to take care of themselves, things like paying the bills, driving, cooking for themselves, dressing themselves. This is really late stage. It happens much later in the progression of the disease. A lot of the neurodegenerative diseases, which are the underlying ideologies of dementia, take 10, 20 years to develop,” said Judy Pa, assistant professor at the Institute for Neuroimaging and Informatics in the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California (USC).

Pa is part of a team of researchers studying the effects of virtual reality on the brain and cognition related to aging. Pa said unlike 2D games, VR provides a first-person, 3D immersive experience that is critical to spatial memory training.

“Our goal is to prevent dementia (and) to prevent Alzheimer’s disease. There are no effective treatments yet. We hope that we will get there eventually, but my perspective and the research that we do in my laboratory at USC is really surrounding prevention,” Pa said.

Targeting risk factors

The VR study targets some of the risk factors of Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive dysfunction, which include a sedentary lifestyle and lack of cognitive and social stimulation. The VR study exercises the participants’ body and brain at the same time, challenging the memory and decision-making part of their brain.

Participants have to pedal on the exercise bike and keep their heart rate up. In the VR experience, they are trying to learn and remember a route while picking up food items by hitting the brakes, then feeding the food to some animals.

“Understanding changes in the brain that happen with exercise, changes in the brain that happen when you’re in an enriched environment and putting those two together, and that’s what our intervention is currently targeting,” Pa said.

Even if virtual reality can help, it may not be for everyone. In a feasibility study, 4 out of 40 people withdrew from the research because of symptoms of motion sickness. Pa will be conducting trials over the next year with participants who are 50 to 80 years old to gather additional data.

Garcia has high hopes for what VR might mean for the future.

“There might be a place where you could go, and you can get your daily dose of virtual reality and cardio to keep the mind going,” he said.

Still, in the early stages of research, the goal is to prevent or even delay the onset of cognitive decline so people can have a solid quality of life during their golden years.