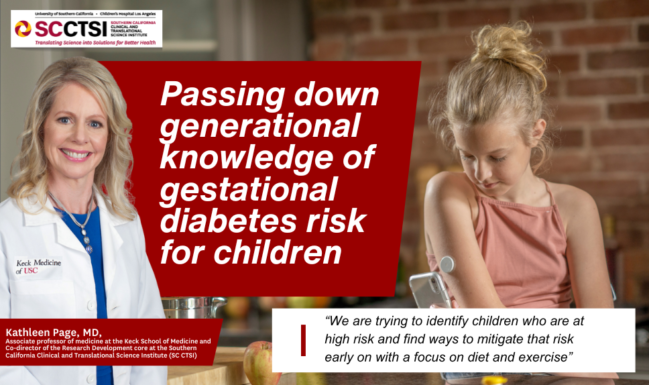

Passing down generational knowledge of gestational diabetes risk for children

Investigations sparked by SC CTSI pilot funding inspire a young research participant to pursue neuroscience as a career.

Charis Alexander hopes that her education and training could someday help science illuminate how people make critical life decisions, an ambition nurtured by her decade-long experience as a clinical research participant at the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California (USC).

Now age 18, Alexander is graduating with a B.S. in neuroscience from USC and enters the Keck School MD/PhD program this fall. She plans to continue as a research participant while following in the footsteps of the neuroscientists she admires.

Alexander was the first participant recruited into the USC BrainChild study. The investigation began in 2014, following 220 children, ages 7 to 11 in the original cohort, from diverse populations in Los Angeles. The research team led by Kathleen Page, MD, an associate professor of medicine at the Keck School of Medicine and Co-director of the Research Development core at the Southern California Clinical and Translational Science Institute (SC CTSI), was the first to identify that exposure in the womb to diagnosed maternal gestational diabetes disrupts a child's metabolisms and brain development.

A mother’s gestational diabetes could increase a child’s risk for obesity and Type 2 diabetes later in life.

“We are trying to identify children who are at high risk and find ways to mitigate that risk early on with a focus on diet and exercise,” said Page, also Co-Director of USC’s Diabetes and Obesity Research Institute (DORI). Researchers collect data on diet, physical activity and sleep using wrist accelerometers and dietary questionnaires.

As for Alexander, participating in the BrainChild study influenced her choice to pursue research as a career. Over the years, she has interacted with the researchers and found them “excited and passionate about their work, trying to answer high-level questions about brain development and decision-making. To me, those questions are so interesting.”

A decade ago, pilot funding from the Southern California Clinical and Translational Science Institute (SC CTSI) helped Page pursue questions about the generational effects of gestational diabetes, a type of diabetes diagnosed in some pregnant women. She also received a KL2 award, which supports early-career development of health professionals, or individuals with research doctoral degrees, in pursuing formal training and careers in clinical and translational research. KL2 fellows receive significant research support and mentorship from SC CTSI staff.

Page’s study shows that gestational diabetes in pregnant mothers affects brain structure and function in their children. Imaging technologies have allowed scientists to observe how the brain responds to pictures of sugary food among exposed children and those not exposed.

“Children of mothers who had gestational diabetes have differences in the hypothalamus and the hippocampus and other areas of the brain that regulate how much we eat and our energy expenditure,” Page added. “We think that if those areas in the brain develop differently, then children respond differently to food. At age 12 to 14, the accrual of fat and BMI growth trajectories among exposed kids are higher or they are gaining weight faster than unexposed kids.”

Ultimately, Page seeks to learn whether children of exposed children are similarly at risk for obesity or diabetes and whether those risks can be mitigated by diet, lifestyle and other interventions over generations.

“The first child we recruited is now 18; that’s Charis,” Page said. “We want to watch the children as they age and potentially have children of their own.”

Alexander hopes to study how people make decisions about their health and other critical aspects of their lives.

“If not for this study, I’d never have known there are differences in our brains that influence which foods we choose to eat,” Alexander said. “That planted a seed in my mind. What are the brain processes that affect how we make decisions, how we interpret the world and act one way or another?”

As a clinical research participant, she hopes to bring her experiences to next-generation labs.

“The staff and graduate students in Dr. Page’s lab always took time to explain what they were doing and why this study was important for the subjects,” Alexander said. “It was never like, ‘I'm going to take your blood now, then off you go.’ You might not realize that how you conduct a study can affect us. We are being watched—that’s a scary way to say it—but it has an impact. As participants, we are seen as people, and as a community, rather than as just subjects to get data from. It’s one of the reasons why I’ve had such a positive experience in the study and why I want to do research as a career.”