SC CTSI develops cartoon robot to help draw cautious, underrepresented minorities into clinical trials

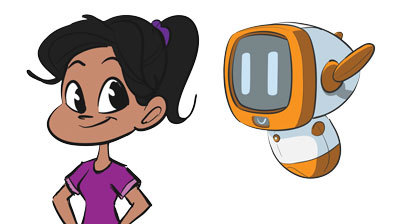

Zippy follows Ava, a teenage patient with diabetes, through the halls of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, hoping to engage her in a conversation about clinical trials.

“Keep your research studies to yourself!” Ava says. “I know what happens. Once you go on a study, you never come back.”

A self-described medical research robot programmed to help humans learn about research studies, Zippy understands Ava’s anxiety. The kind and well-meaning robot praises Ava’s skepticism and tries to alleviate her fears by explaining the rights and protections assured to participants in clinical trials. Zippy is presented as a helper, not as a doctor or nurse, nor with any particular identity, so the information the robot provides is better received by a distrustful teen.

In spite of herself, Ava is intrigued. “I have more questions,” she says. “I have more answers,” Zippy replies. The two walk off together, continuing their dialogue. Whether she says yes or no to participating in a research study, Ava will have the information she needs to make an informed choice, and Zippy will have done its job.

Although this is a scripted cartoon being played out on a YouTube page, it’s the hope of Michele Kipke, PhD, and her team at The Saban Research Institute of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles that it will be repeated in real-life encounters. Kipke, the hospital’s vice chair of Research in the Department of Pediatrics, is counting on Zippy’s wisdom, empathy and charm to increase diversity in enrollment in CHLA’s research studies, where white participants outnumber participants of color by 4-to-1.

“As a result, our clinical trials don’t provide enough information about the health of communities of color,” Kipke says, “and we don’t know if we’re going to get the same positive benefits in African-American or Latino populations.”

This isn’t a problem specific to pediatric studies or to CHLA. Kipke says minorities are also underrepresented in adult research studies nationwide.

Patients from minority communities have long been reluctant to participate in research, due in part to a history of abuse in past studies. Kipke cites the most egregious examples, such as the Tuskegee Airmen—African-American World War II pilots who were experimented on without their knowledge—and Henrietta Lacks, an African- American woman who, in 1951, did not consent to the use of her cells, which are still being used in cancer research today.

Kipke says conversations with local families have confirmed that suspicions persist, even though the research process is now highly regulated and includes many patient protections. Although researchers—including Kipke—are working to correct the imbalances in clinical trials by increasing participation among communities of color, those changes don’t happen easily or quickly.

“We know patients are mistrustful,” Kipke says. “They’re also afraid of some sort of unintended consequences occurring down the road. What they don’t know is that they have rights as participants. We need to shed light on the protections for patients while explaining the importance of research to families.”

Enter Zippy, Ava and other supporting players in a series of videos developed through the Virtual Research Navigator Project. The videos are looking to build what Kipke terms “research literacy,” a better understanding of what research studies are and a greater willingness among patients to join them. If families have questions that aren’t addressed in the videos, Zippy can respond to their queries through a website. Kipke and her team developed the content working with engineers and animators at USC’s Institute for Creative Technologies, within the university’s Viterbi School of Engineering.

The videos are essentially animated tutorials well-disguised as cute narratives. In each, the polite but earnest robot Zippy interacts with Ava, your classic eye-rolling teen, and her parents—addressing their concerns about clinical studies and taking on issues of privacy, enrollment, consent and the importance of research participation.

In one video, titled “Benefits,” Ava shuts down Zippy’s pleas. “Save your battery,” she says. When Ava expresses concern about being part of a research study, Zippy explains the protections in place, but doesn’t push. “Do what you feel is right,” the robot says.

Ava comes around: “OK, I can at least listen to what the doctor has to say.”

And that, Kipke says, is her goal for the videos. She’s not looking for an instant yes from families, but rather hoping to provide them with the resources to make an informed decision, “so that when they’re sitting with their pediatrician who says, ‘Your daughter with type 2 diabetes would be eligible for this clinical trial,’ they are more willing to listen.”

Kipke’s team has completed the pilot phase of the project and is now moving ahead with making some adaptations to the platform for use in multiple children’s hospitals in the U.S.

Although diversity among research participants has been a longstanding problem, Kipke says it has taken on more importance as health care moves toward precision medicine. “We’re trying to figure out what works best for whom, and why, and in which real-world health care settings. The only way we can do that is if we have data from everybody.”

That may be ambitious, but it’s only a means to Kipke’s ultimate objective, which is to accelerate the research pipeline—the course from discovery in the lab to actively improving child health.

That effort is the ongoing work of the Southern California Clinical and Translational Science Institute, another collaboration between CHLA and USC, underwritten by a $36.6 million grant from the National Institutes of Health.

On average it takes 20 years for new breakthroughs to be translated into treatments and then put into use. “That’s too long,” Kipke says. Testing medications and other treatments for safety and efficacy is crucial, but the process needs to be shortened and barriers to getting people into research studies—such as their fear and mistrust—need to be eliminated.

“If the goal is to speed up the research pipeline, part of that is how you engage people in clinical trials,” Kipke says.

And if Zippy is successful at its job, “people” will include everyone.

To find out more about this work, visit CHLA.org/KipkeLab